Bikes

From Air Force to beach cruisers

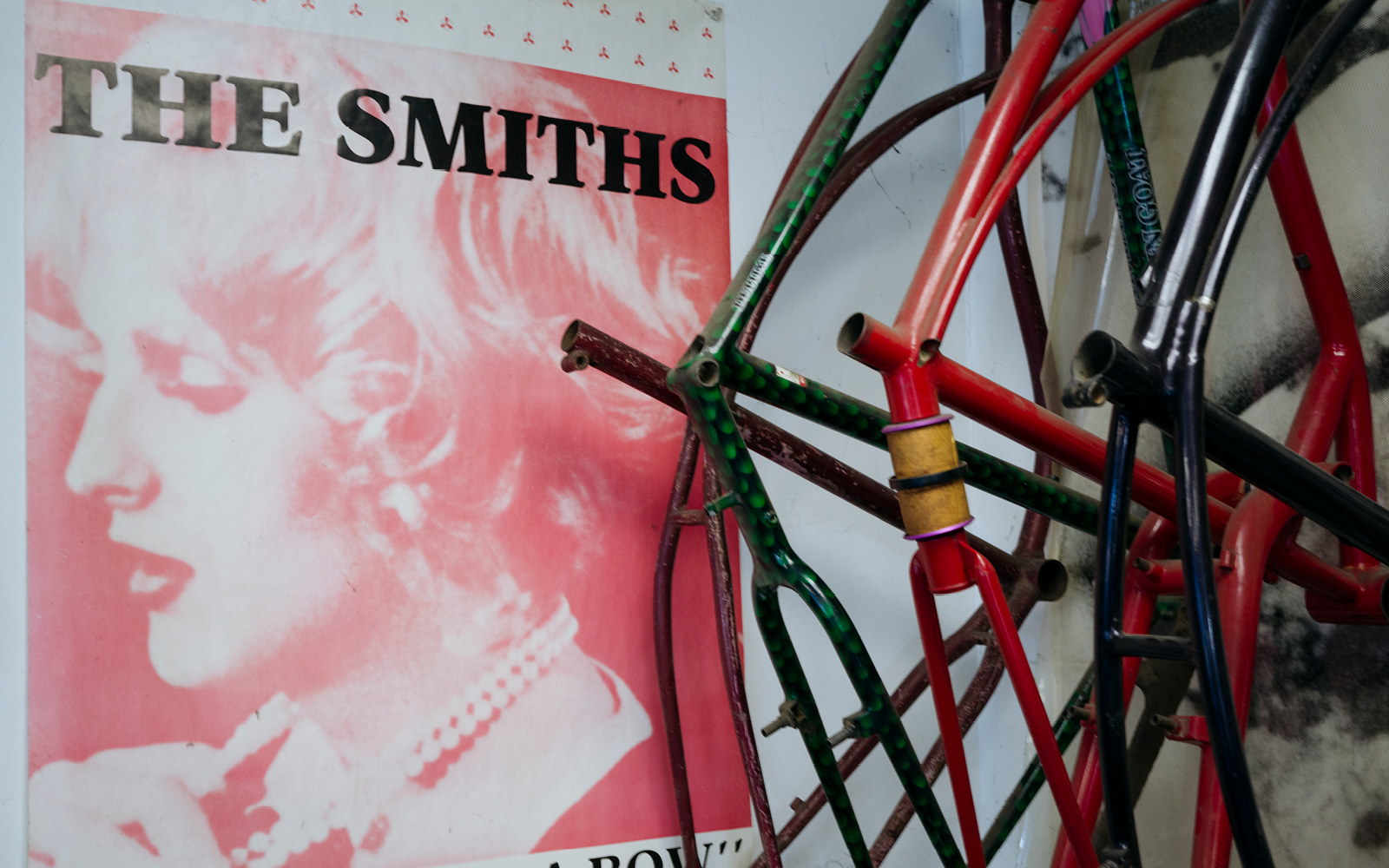

Retrotec / Inglis proprietor, Curtis Inglis, tells Brooks about his journey through framebuilding

By Kit Nicholson

Curtis Inglis has been building steel bikes out of California since 1993, meaning he has almost thirty years of experience in an ever-changing industry.

Like his customers, Inglis was drawn to Retrotec’s distinctive beach cruiser design, and over the past 28 years, he’s developed the brand’s unique twin top tube feature, and set up a straight tube frame strand under his own name. Each brand informs the other, sharing the curved arches that set them apart.

Retrotec was started in 1992 by Bob Seals. A year later, Inglis started working for Seals.

“I’d seen the Retrotec bikes at a bike race and it blew my mind to see a beach cruiser going head to head with all these super light race bikes. It was pretty amazing to see the stark difference. You can still have fun and a slight joke about what a bike should look like in racing. I fell in love with them and went begging for a job.”

He was in luck. Seals’ welder had just left and he needed someone to take over the building process for him.

“I had been a welder in the Air Force prior to that and I’d just gotten done with a two-year degree in drafting, so both those things definitely helped me slide into the job, especially the welding experience. I lived up at his house in Chico and built bikes out of the ranch.”

After three years in Chico, Inglis wanted to move to the Bay Area and get set up in San Francisco.

He continued to work together with Sears, Inglis responsible for all the bike building while Sears ran the company, until Inglis took over the whole operation.

“Retrotec started with just one style which was the pretty standard beach cruiser, cantilever frame. And that was Bob’s baby. As I took over more of the frame building, I wanted to come up with a few different styles which were a bit lighter, and to make a bike with a straight downtube instead of the S-bend downtube, and then the extra two or three tubes. I wanted to be able to make them quicker so I could build up production a bit.”

Ultimately, you tend to build what you have the ability to build. You can dream up whatever you want, but if you can’t physically make it…

Inglis was mindful of Retrotec’s origins – classic cruiser style with modern geometry – while coming up with new ideas. He drew inspiration from what he saw locked up around town.

“Everything I came up with played on the same original theme and they’re inspired by the different bikes that I saw around. Chico was a college town and you’d see cruiser bikes locked up. So all the new styles would have a nice flowing line from the dropout to the head tube, like the cantilever frame that has a really arched look to it.”

The distinctive arc presents an interesting challenge, especially in varying bike sizes. The arc is much shallower on a smaller bike compared to a taller person’s, which has a bigger head tube and seat tube, making the arc much more “bubbly”.

“The challenge is trying to give the smaller riders a good stand over clearance and the taller riders don’t want to have a ton of seat post showing. And they’re all different. The arcs on the top tube and seat stays need to meet and look really natural. It’s a constant process of making sure that it all flows really well and has a nice look to it.”

A smaller bike uses less material and tighter geometry which can potentially lead to a more rigid and stiff ride compared to larger frames of the same design. Ride feel also varies according to the rider’s style and physical attributes, but there are ways Inglis can mitigate that.

“In every tube there are two or three different wall thicknesses I can use, so each of those correspond with the riding style, how heavy they are, if they’re known to break their bikes constantly. If someone comes to you who breaks everything, you don’t want to build the lightest frame, you oversize everything just a hair. Those are just some of the questions you ask before you start.”

After a few years, Inglis added a new strand to his frame building, namely a range of bikes under his own brand. It was initially a sort of backup plan in case Retrotec took a different route or something happened that meant he’d be required to go in a different direction. Ultimately, Inglis was wary of putting all his eggs into a single basket that was not his own. Now though, it’s simply a differentiation between straight (Inglis) and curved (Retrotec) bike frames.

“Inglis started mainly with straight tubes, but even then, the seat stays are really curvy and very unique. Ultimately, you tend to build what you have the ability to build. You can dream up whatever you want, but if you can’t physically make it… I’m known for really big arcs. I have a certain type of roller and bending apparatus that started with Retrotec, which is different from what someone who does really tight bends will use. They can’t do a big radius like I can, and I can’t do the real tight stuff. You build what you’re able to.”

Wrapped up in ‘build what you’re able to’ is a process of constant reaction and development as the industry evolves and standards change. After 28 years of experience in frame building, Inglis still finds it fun and intriguing to watch change happen.

“Sometimes there will be a new standard that feels like a downgrade for us in steel and then we have to figure out a way to make it work. Like when flat mount [for brakes] came out, that was a huge ‘oh gosh, this is going to be horrible’ moment. But so many neat little tricks have come out of that. So things always evolve and at first it’s hard to stomach, but we always move forward. It’s really fun to stay on top of that.”

Three quarters of the bikes Inglis builds are in the Retrotec range, with seven styles forming the “meat and potatoes” of his work. But occasionally a customer comes in with their own idea based on one of the styles, perhaps with extra ‘beauty tubes’ on top of (or underneath) the traditional single top tube.

“As long as it’s something that I can do within a reasonable amount of time, the biggest thing is making sure that the bike is going to be rideable and safe and last a long time. As long as I can make it work for the customer, then there’s a lot of leeway for what someone wants.”

It’s very normal for Inglis clients to use the word ‘light’ when describing the custom bike they want, just like customers throughout the cycling industry. ‘Lightweight’ has become an aspirational value, but it’s not the pinnacle for Inglis.

“The lightest bike that I do is the Retrotec Half with the single top tube. It still has a nice cruiser look to it, but most people want a twin top tube. So I always tell people that for the small amount of weight gain in that twin top tube, you might as well go with the bike you dream about at night, not the lightest lightest, lightest, lightest frame.”

After all, there’s something Retrotec and Inglis customers tend to have in common.

“The people buying my bikes already own a bike, but what I’m trying to do is build them a bike that fits better and makes them want to pull the Retrotec off the wall instead of the carbon race bike. We’ve been around long enough that our customers might have seen their first Retrotec when they were in college or high school. Now they’ve got a job, raised a couple of kids, and now they’re in their fifties and finally want to buy this thing that they’ve found is still produced.”

While neither Retrotec nor Inglis have ever sought to be ‘on trend bikes’, the industry is constantly evolving and their output varies accordingly.

“The bikes change as the industry changes. There was a point when I was building a ton of one-speeds because one-speeding was the thing, right? And then it was town bikes, piles of town bikes. And now, I build a lot of gravel bikes. The one constant has been mountain bikes just because that’s where we came from and people still see that as our thing.”

I think there’ll be some version of custom bikes forever. I enjoy having that interaction with a person and then building something for them.

In 2008, Inglis was instrumental in bringing the Single Speed World Championships to his home trails of California. It meant travelling to Sweden to pitch the destination, rather like cities hoping to host the Olympic Games, and then organising the event itself. They opted to restrict the number of participants to 300: 100 from California, 100 from the USA and 100 international riders. It was a popular but “rocky registration” process, but it was all worth it when the event came around.

“It was a lot of work and it’s something you should definitely only do once before letting somebody else deal with all that. But to be able to host bike industry friends or just friends we’d met at races over the years, it was great to have them in California and to show them the best trails. It was a week of riding your brains out all over the Bay Area. We only did it because other countries had done it before us. And whenever I get the chance, I still like to go.”

It seems Inglis is a sucker for punishment, always looking for a challenge. Frame building is after all a constant exercise in problem solving. Industry innovations can throw up complications at first, but it’s all an opportunity to evolve. Inglis is not about to stop and get stuck in a rut. He’s having too much fun.

“As a cyclist that still enjoys riding and enjoys seeing what those new innovations give us, it’s really fun to incorporate that stuff into building. I’m not positive where things are going, but I think there’ll be some version of custom bikes forever. I enjoy having that interaction with a person and then building something for them.”

Visit Inglis Cycles for more info.

Featured Products

More Bikes Stories

“Design is everything” – Fairlight Cycles

Discover the bikes that sell themselves, designed by Dom Thomas and the Fairlight team.

READ MORE