Journeys

The Valley at the Roof of the World

Four cyclists, a trip to the roof of the world

By Tom Owen

Some adventures are all about discovery, some about racing from one place to another, but others have far simpler goals. Tom Jamieson undertook a journey through India with three companions, straying way beyond the beaten track and finding themselves in areas so remote that they were the first strangers the locals had seen in months.

Jamieson’s was an adventure that celebrated the simplicity of life on two wheels and he experienced some spectacular cycling along the way, not to mention the conditions. The landscapes too were like nothing else and Jamieson, a photographer by trade, was able to take full advantage of his surroundings, bringing home a stunning collection of photographs.

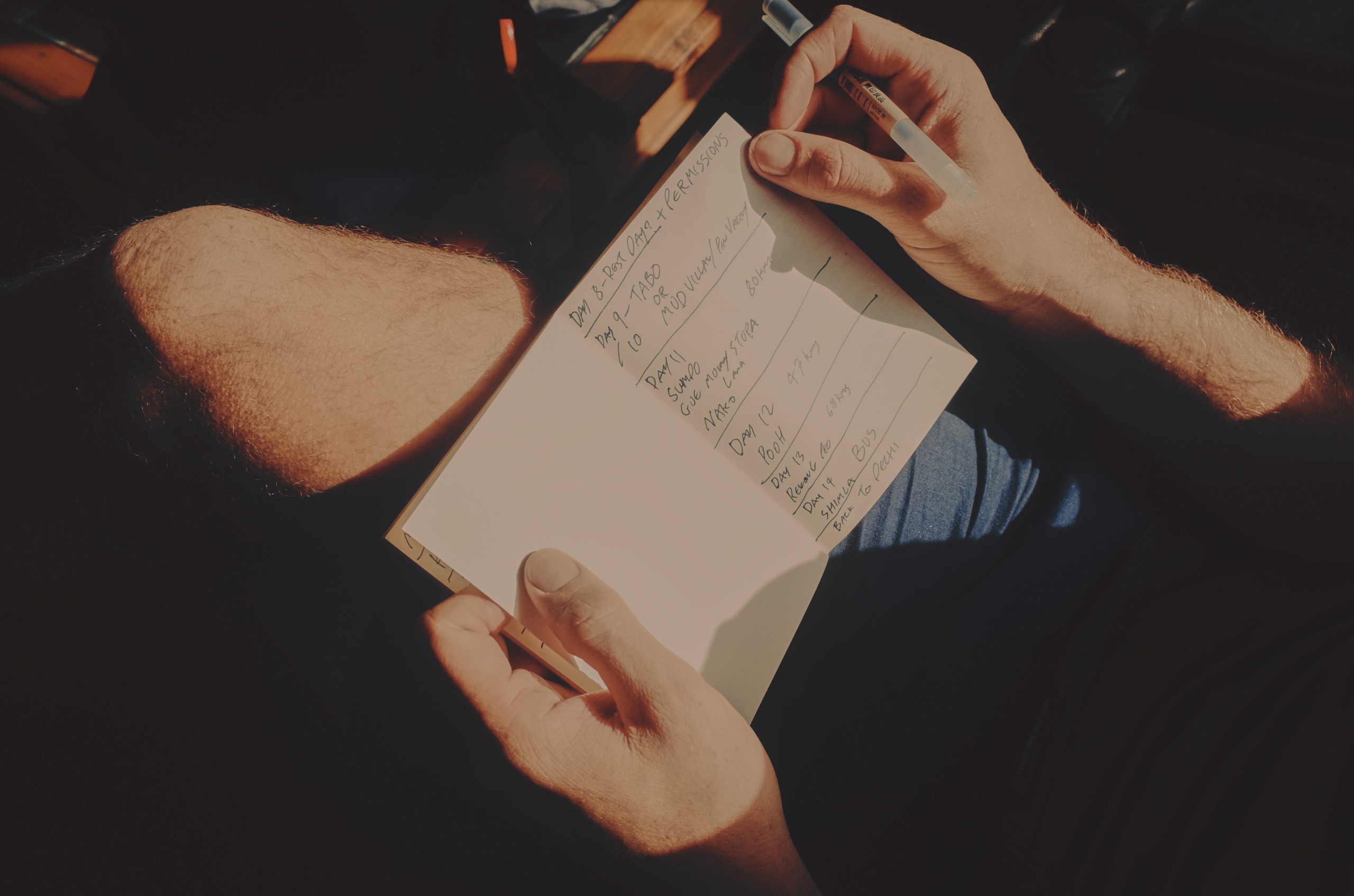

The group’s tour started in Manali, took them over the Rohtang (3976m) and Kunzum (4590m) passes, through glacial water, boulder fields and 10,000-strong crowds of tourists, and into the glorious Spiti Valley before finishing on the road to Tabo. The worrisome words of local farmers who warned they’d risk death if they continued hung over them as they pushed their bikes through the snow, but they persevered and won the battle against the elements, the doubters and their own minds.

Tom Owen talked to Jamieson about how the adventure was conceived, how he dealt with the significant hurdles encountered on the road, and what he discovered along the way, about cycling, the unfamiliar environment and about himself.

How did the idea come about?

It came from my friend Karan who lives in Delhi. We met on a photography workshop in Istanbul about 10 years ago. We’ve got quite a lot in common – we both ride bikes, we both ride motorbikes, we’re both photographers. He’s been trying to get me out there to do this trip for the last three years. I finally decided that 2019 was going to be the year to actually get it done. He’s done similar trips, treks on motorbikes, but not a proper bicycle tour. So, off we went!

It’s fair to say there were times when you were pretty remote, when you couldn’t actually ride your bikes. Is that right?

Yeah. Looking back it probably made the trip, but it wasn’t easy.

The snow’s normally gone by the beginning of May so all those roads up there heading towards Ladakh and Leh were meant to be clear. We were expecting to get some sweet cycling, but the snow was all still there midway through June. Some of the roads – the ones the army uses to get up to Kashmir – are maintained all year round so they were fine. But where we were going, Spiti Valley, is fairly remote. We spent four days on the approach, stopping whoever we could on our way up, from tour guides to locals on tractors. We were told everything from “you’ll die” to “the road’s open”. We decided to carry on and see for ourselves and as it turned out, nobody was completely right or wrong.

We had three days where the Indian army were clearing snow from both sides of the road. Depending on which side of the mountain we were on, we either had huge 15-20-foot snowdrifts which hadn’t been cleared at all, or we had these boulder fields which had come down through the winter and destroyed the roads. So, we had two or three days of hike-a-biking, pushing over snow or rocky terrain, interspersed with brief stretches back on our bikes.

This was just three days of the whole trip, and when we got to the other side the Indian army were saying, “What the hell are you doing? You have bicycles? What’s wrong with you?” In hindsight it was the worst bit, everyone was swearing under their breath for two days, but it was what made it into a real adventure.

My favourite photo is the one where you’re inside the shop and you’ve managed to catch the guy’s face in the light. It made me wonder about your impression of the people in that environment. What sense did you get of their lives?

We really didn’t see that many people until we got properly into the valley. We’d see the odd shepherd, but they had these roadside restaurants called dhabas dotted around. The dhaba where the picture was taken is not that far from Manali, but there were others where I’m sure we were the first people they’d seen in three or four months. They’ve been waiting for the winter to clear – up there the roads are impassable until May – and monsoon season starts in July. They’ve basically got just six weeks to make their money for the year.

The people we met, especially in Spiti, were just amazing. Everyone was so friendly, they all wanted to talk to you. It really is in the middle of nowhere – we’re talking generators for electricity, no internet, no phone reception.

Just nothing, completely out in the wilderness. You’re right up on the border between China and India, but not the populated part. It was crazy – exactly what we were after; we wanted a real adventure away from everything and that’s exactly what we got.

Did riding your bike or shooting photographs up there give you any particular challenges?

I fell off my bike once, but that was down to my own stupidity. Two of the guys had fat bikes, which in hindsight were way better suited, and the others were gravel bikes. But shooting wise, not really. Everything was a photograph. It’s not hard to take good pictures in a place like that. I think each night we managed to up the stakes in the ‘impressiveness’ of the campsite. It was totally, totally unreal.

And it was quiet. I think the most important thing was just switching off, which was exactly what we wanted. You can turn your phone off, but having the connectivity actually taken away from you, not being able to check your emails if you wanted to, was pretty awesome. It took about 48 hours to get over the anxiety of that, but once we did, it was great. Selfishly, I don’t think I thought about anything or anyone else other than the trip while I was on it. It was pretty special – no outside engagement, no nothing.

It looks from the photos like there were some interesting footwear choices given the conditions. Who was wearing sandals for this?

Everyone had sandals and two of us had cycle shoes as well. That picture of someone with sandals and dry bags on their feet – we all had a pretty similar setup. It’s not exactly the best thing for going over a snow-covered pass though! We’d all gone there on the understanding that the roads would have been open for a month already, but as you can see, it was a very different story.

Where did the adventure start?

We flew into Delhi, followed by an arduous 14-hour bus journey to Manali at 2,050m. That’s where we started, and as an old hill station full of tourists, it was really busy. The first pass we had to get over was Rohtang which is a little further up the road and took us to 4,000m. It’s a little strange – Rohtang is where thousands of Indian tourists go to see snow. There’s snow there all year round, and I’ve never been on such a congested road. It was a traffic jam thousands of cars long, people everywhere taking selfies and everyone wearing these ’80s style all-in-one ski suits. There are shops in Manali that rent them out but it was around 25 degrees – no need for ski suits!

Then as soon as you get over that pass, there are no more people. That’s as far as anyone goes. Then we went from Rohtang to Gramphu, to Chhatru and to Batal. After that you’ve got Kunzum Stupas and that’s where all the snow was. That’s where we got stuck.

So we pushed the bikes for a few days, and once we were over the pass we were in to Spiti Valley, which is an amazing valley running along the river. It’s like being on the surface of the moon – if it wasn’t for the small patches of snow on the peaks you’d think you were on Mars or something. It was a really strange, dry, high-altitude desert. The majority of the trip was exploring around there, up little offshoots and valleys. After 10-12 days cycling through there, we got spat out the other end…

It was one of those amazing things. You just get up, pack up your tent, get on your bicycle for eight hours, unpack your tent and sleep like a child for eight or nine hours. And repeat. It was fantastic, absolutely fantastic.

Did you see any other cyclists? How was the reception?

No. The major town in the Spiti Valley is Kaza and there are a couple of hotels there, but within about a day of arriving we were local celebrities, these stupid cyclists who had come over the pass when no one else could. We saw one couple from France on MTBs who had ridden all the way from Beijing, and they were going to give the pass a go, but other than that we were the only ones there. Pretty wild in retrospect.

The cycling was insane. We’d have days when we’d be riding over passes which would take all day to climb, and other days would be completely flat, on tarmac or really fast gravel. We’d have 80-100km days, followed by just 30km. It was all changeable; it was like cycling on another planet. As soon as we got over that first pass, where I was quite concerned with all those people in ski suits, it was just incredible.

On the old army roads to Leh and to Kashmir, it seemed you could go on forever. The only thing that was a bit tricky was that we needed passes or permits, which we didn’t always have. I think with variables that were out of our control, like altitude sickness, we got away really lightly. We were able to get up and ride the bike every day, which is what we went for.

What was the ‘roof of the world’ like?

It’s definitely a very spiritual place and two of the people on the trip were seeking that. For me, I’m not sure that the feeling necessarily came from the place itself, with its monasteries and a long history of spirituality, I think it came more from what we were doing. The contentment and peacefulness came from riding our bikes.

You know what it’s like when you go on a long bike ride; you go into your mind, into this strange zone? If you’re doing that for seven, eight hours a day for weeks on end, and you’re not thinking about getting hit by a car, you tune into something different. I think any kind of stillness and contentment came from being on the bike.

Tom Jamieson’s essentials

More Journeys Stories

The land of powerful mixtures

West Africa’s untapped wonderland – discovering Sierra Leone gravel

READ MORE